My Visit to Newly Renovated Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum

Ms. Reiko Horimukai

Public Relations and Publications Office

The “Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum Renovation Project” was completed on April 25, 2019, following around 12 years of formal planning. The Main Building first opened in 1955, but had been closed since 2017 for the renovation, including reinforcement work to protect against earthquakes. Displays and exhibits underwent their first major renovation since 1991.

My work at RERF as a staff of the Public Relations and Publications Office means I often deal with the issue of communicating information about A-bomb radiation health effects to the public. To improve our own techniques, I decided to learn how the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum went about animating the history of the atomic bombing and the suffering of the survivors in a way that invites and informs viewers.

I thus recently, on May 10, took a half-day trek to view the exhibits. I came away with greater understanding about the A-bomb survivor experience but also emotionally spent.

After my visit, I felt keenly that the Museum’s presentations of A-bomb survivors’ experiences and RERF’s focus on radiation health-effects research can play important roles in keeping history alive, even after the survivors and their children pass from the scene. In that way, both organizations are working to achieve similar goals.

The following descriptions are based on notes about what I saw on my visit. I especially want to encourage everyone to visit the Museum.

Museum’s renovated Main Building

East Building: Ruins of the city

When taking the long escalator in the Museum’s East Building with all the Japanese students there on school trips, a panoramic photograph of pre-war Hiroshima gradually unfolds before us. On the walls are also photographs of the stately Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall (present-day Atomic Bomb Dome), scenes of the town of Nakajima-cho with its continuous rows of tiled roofs (located around the current Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park), a bustling shopping area, a commemorative photograph showing an elementary school with joyfully smiling students, and more. I gazed upon these photographs aware of the uncertainty of people’s daily lives as the shadow of war slowly grew nearer.

The next section in the East Building comprises photographs on the walls of the city of Hiroshima 2-3 months after the atomic bombing. There truly was almost nothing left. Only the remains of concrete buildings and towers endured. Trees that had become only trunks stood forlornly. (To imagine all this destruction was from a single weapon…)

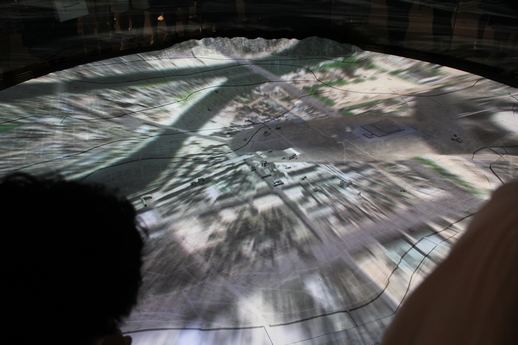

In the darkness of this section of the Museum is a video of Hiroshima at the time of the bombing. Shown is the city from a birds-eye view. Then a single bomb appears and falls; the next moment, the lush green delta area is enveloped in a flash and the city destroyed. The blast from the explosion spreads out over the area, which is covered with thick smoke. One wonders how many people were injured and died under the cover of this cloud; the school children and the city residents in the shopping street seen in the previous photographs naturally come to mind.

Before this renovation, the museum used a display with only a red light hanging over a model of Hiroshima to suggest the atomic blast. But with new computer graphics, viewers cannot help but feel immersed in the reality of the blast and undulating black smoke, a sensation that had me jumping back instinctively. (If RERF could produce such videos, I wondered, might it be easy to create readily understandable explanations about all sorts of topics, for example…)

Video of the atomic bomb being dropped on Hiroshima

Main Building: Reality of the atomic bombing ? Personal stories

From this point on, the Museum takes a personal look at the reality of the atomic bombing. The exhibits contain the valuables of those in their early teenage years who had been mobilized away from home to help make fire lanes in the city, as well as descriptions and notes from the family of each of the victims. Each person’s name and situation at the time of the bombing are exhibited here, along with clothing left in tatters by the bombing. One of those was a female student who had, after much struggle, finally arrived at her house with the expectation of reuniting with her family; another was a male student who died asking a passerby to take a memento to his family; yet another was a mother who continued to wait for her child’s return for many years after the atomic bombing; there also was an uneaten mother’s handmade obento (in a situation marked by scarcity of food, the mother seems to have done her best to make her child an obento of favorite food). The displays of personal items and notes revealing the surviving families’ emotional devastation are heartrending. The students on a school trip who had been chatting until this point grew silent and began to tear up while reading the descriptions. They seem to have felt in their souls the sorrow and sadness of those whose lives had been so easily taken at around the same young age.

Torn clothes

Charred obento (right)??

Photo courtesy of Ms. Shigeko Orimen

The next room is designed for paintings and testimonies depicted by atomic bomb survivors. One painting shows roaring flames and charred corpses; another painting conveys the image of a ghost-like person with peeling skin; another painting depicts a mother desperately calling her child’s name as countless corpses float by in a river. Recollection of such scenes had to been painful for these survivors. They likely developed a sense of mission from their realization that the scope and horror of this disaster must be conveyed to following generations, as well as from a feeling of regret that they were not of any use to those in need of help who had suffered so profoundly. Here, the enormous life energy of each of the survivors was simply overwhelming.

Paintings created by A-bomb survivors

There were certain things in paintings and photographs of city first-aid shelters that simply could not be viewed directly. One example was a photograph of a female student with burns on her entire face such that the viewer could not identify her eyes, nose, or mouth; and a painting of a student holding in an eye that had popped out (Is the presence of such a hell acceptable in our world?). I put one foot in front of the other with tears running down my cheeks and my nose running. Sobs of overseas women could be heard to the rear (there are no borders for sadness and anger). When looking at the scenes of rescuers treating others while injured, I recall that ABCC*―RERF was frequently accused of “conducting research but not providing treatment.” Couldn’t we in those days have done more for the survivors in terms of treatment, considering the various circumstances at that time? I ask this question again as a human being.

Nuclear reality

On the return from the Main Building to the East Building was an exhibit on the nuclear threat. From that, I understand that now on earth there exist about 16,000 nuclear weapons. On the other hand, despite the calls for abolition of these weapons, any nation that wants them can persist in its effort to acquire them. I cannot help but feel that more voices from Hiroshima need to be expressed and heard.

Models of Hiroshima and Nagasaki A-bombs

The museum renovation resulted in the inclusion of an exhibit of photographs of the chromosomes of an A-bomb survivor named Mitsuo Kodama. Visitors can observe this chromosome exhibit by selecting it from among the files presented on computers located on a media table. In short, Mr. Kodama was exposed at a distance of about 850 meters from the hypocenter to 4 gray of radiation, a very large dose. Very few people at that distance survived the bombing’s effects. There are 10 abnormalities in Mr. Kodama’s chromosomes, with five translocations clearly apparent (translocation means that a section of a chromosome is cut and adheres to or fuses with a different section of the same chromosome or another chromosome). Mr. Kodama, one of the atomic bomb survivors who actively convey the reality of the atomic bombing by speaking of their own personal experiences, has undergone more than 20 cancer surgeries. From RERF’s perspective, in this way scientific explanations of radiation and its effects on the human body comprise one of the atomic bombed cities’ most important roles.

As a staff of the RERF Public Relations and Publications Office

RERF research looks at large populations to explore radiation’s health effects. Epidemiological studies such as the 120,000 Life Span Study and the 77,000 Children of Atomic-bomb Survivors (F1) Study are crucial. Such research is used to calculate accurate population data, which are adopted by the International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP), and other organizations, to protect people around the world from harmful effects of radiation, in airports, in the doctor’s office, or in space, to name a few examples. I think this is amazing work, and I’m proud to be part of it.

But wait a minute: what must be remembered is that the tens of thousands of atomic bombing victims each had a precious name bequeathed to them by their parents, an identity, a beloved family, a promising future. With this in mind, RERF must continue its work to provide facility tours as a “kataribe(storyteller of the A-bombing experience) of the science of atomic bomb radiation health effects.” This is the conclusion I reached following my facility tour of the Museum.

The A-bomb survivors’ stories reminded me to get back to basics and to work. At that point, I turned around and left behind the Museum crowded with students and overseas tourists.

A-bomb Dome and Cenotaph (in foreground)

*ABCC

The Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission, established in 1947, was the predecessor organization to RERF. ABCC was a U.S.-led scientific organization, but in 1975, it was restructured into RERF, which is jointly managed by Japan and the U.S.