Reminiscences

by Kimie Fujimoto

Receptionist, Hiroshima, 1948-1965

In November 1946, I learned from the news on the radio that a free health examination was being provided at the Hiroshima Prefectural Hospital. I promptly visited the hospital for examination and found many people waiting in the hope of regaining health with the help of medical science. I noticed a man working busily as an interpreter and receptionist.

There was no one to take care of the female patients there, and unexpectedly, Dr. Snell asked me to help them as a receptionist during the examination period. Thus I started working at the hospital every day. How often did I feel desolated while I walked through a wide stretch of burnt ruins in the evening back to Koi-machi, where there were many family houses, and had to cheer myself up with the thought of providing what little help I could to the many patients who sought medical care.

For the next few months, ABCC conducted its activities in the Japan Red-Cross Hospital. Thanks to the cheerful efforts of Dr. Takeshima of the Japan Red-Cross Hospital and with the help of Mr. Nitta, the first three American doctors of ABCC, Drs. Neel, Snell, and Black started to work in the three barren rooms made available.

It was when “contactors” were being recruited that Dr. Snell offered me a position of a regular employee. If my memory is correct, three men were employed as contactors on January 5, 1948. One of them was Mr. Isao Moriyama (Administration Office). The four contactors, including myself, visited A-bomb survivors in the afternoon to make appointments with the fixed number of 25 patients accepted for the examination in the next morning. As the means of transportation in those days only one jeep and one three-quarter-ton truck were available. Since the two vehicles had to be used by the American doctors for public relations activities and also for patient transportation, buying food and other daily necessities, the mood of the driver, a second-generation Japanese American, and Mr. Takahashi mattered to us.

The four of us would get in one truck, and get off at the designated location most convenient for our work. From there we would walk to the houses of the A-bomb survivors we were expected to cover each day to make appointments. We prearranged the time for returning to the Red-Cross Hospital, came back to the designated location at that time, again got in the truck, returned to the hospital, and made preparations for the next day. I remember I was always busy; I sometimes walked up to the top of the mountain in Kure and was always running while working. However, I did not mind how busy I was in those days.

Two months later, I was transferred as a receptionist and assigned a desk job. Examinations were conducted only in the morning. One Japanese physician was responsible for the examination of 25 patients. I completed the forms in which each patient’s name, date of birth, exposure site, clothes they wore at the time of exposure and other information were entered and escorted them to the next examination room. My work was either expedited or delayed, depending on how cooperative the patients were.

Since A-bomb survivors were examined in Hiroshima and their controls in Kure, I worked in both cities alternately.

In those early days of ABCC, when facilities, equipment, and staff were in short supply, we made rounds of the few shops which stood here and there in the ruins in a jeep to buy cover glasses and slide glasses for microscopes. I also remember the time I accompanied my superiors on their trip to negotiate for ABCC relaxation of the restrictions on power supply. Many differences were observed between the Eastern and Western ways of doing business until ABCC, as a research institution, came to be managed in a way Dr. Snell desired. At times of such difficulty, the efforts and understanding of all the people concerned gave me joy beyond measure.

Apparently, Miss Uemura and Miss Nakagawa of the Nursing Section thought that I was too strict about the change of linens. Miss Nakagawa, who is now Mrs. Miller, must by now be fully adapted to the American way of life. The whole staff were supposed to undergo hematological examinations once in three months. Probably because of having suffered from a food shortage for a long time, I sometimes experienced a decrease of blood sedimentation rate by as much as 25 mm in an hour. I recall wistfully that in those days, I was burning with zeal every day to devote myself to work to the point that the work next day did not bother me at all after making clothes to wear tomorrow until 12 o’clock, the previous midnight.

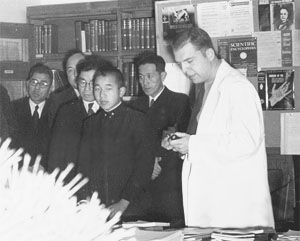

Director Carl F. Tessmer guides Prince Akihito through the facility of Gaisen-kan (the Hall of Triumph for the former Japanese army).

The place and job description of the receptionists have changed year after year. When I first heard that the main building of ABCC would be newly constructed, it seemed to me like a dream far away. Time seems to have passed very quickly because I was carried away by work every day, hoping that I could be of some help in the health examination of patients. I fondly remember the people who had left ABCC, thinking that ABCC might be closed even tomorrow.

This article was originally published in ABCC Newsletter 1(7):5, 1963 in Japanese.