Unprecedented Challenge Faced in Early Years

by James V. Neel

Professor Emeritus of Human Genetics and Internal Medicine,

University of Michigan Medical School

With no comparable project to emulate, the founders of ABCC-RERF ventured into new scientific, administrative, and cross-cultural arenas.

In 1946, Jim Neel never dreamed he would still be involved in ABCC work 43 years later. Right, the author lecturing at RERF in 1983.

Those who currently work at or visit RERF and who have come to know its various resources and smoothly functioning programs would have great difficulty in visualizing its early days. Unfortunately, to my knowledge, all of the original Japanese employees and associates of the then ABCC have now retired; no one is left with firsthand knowledge of the challenges faced in developing the present program.

The first organized attempt to follow up on the effects of the atomic bombings was in September 1945, when teams from the U.S. Army, Navy, and Air Force joined with a Japanese team to evaluate the immediate aftereffects of the exposures. This group, usually referred to as the Joint Commission, issued a report in mid-1946 which included a recommendation that some provision be made for long-term follow-up. It was further suggested that the most suitable U.S. agency for this involvement would be the National Academy of Sciences. The Academy was and is a quasi-governmental agency, a link between civilian and government science, and so, was in a unique position to coordinate such an undertaking. This recommendation was ultimately accepted by President Harry S Truman, and the Academy–as the first step in meeting this new responsibility–decided to send several consultants to Japan.

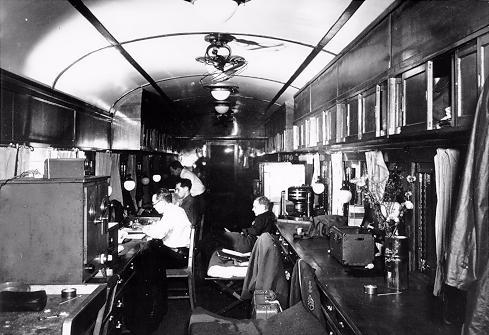

The Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission began as a survey team that traveled throughout war-devastated Japan in the 406th Medical General Laboratory–three railroad cars that were picked up on schedule and attached to the Allied Limited train. Left, the author, who is seated on a cot, Tokyo Univeristy Surgery Professor Masao Tsuzuki, Melvin Block and Austin Brues are at work in thier mobile laboratory, which also doubled as sleeping quarters.

My own contacts with the undertaking began in November 1946. I was then in the Medical Corps of the U.S. Army; suddenly I was assigned to accompany two civilian consultants selected by the Academy, Dr. Austin Brues and Dr. Paul Henshaw, on their mission, as were two other young medical officers, First Lt. Melvin Block and Lt. (j.g.) Frederick Ullrich. My assignment was, in part, based on the fact that I was the only medical officer in the U.S. Army with a Ph.D. in genetics, and it was understood from the outset that I had particular responsibilities related to possible genetics studies.

In its earliest days, ABCC consulted with a wide spectrum of Japanese scientists who were interested in radiation effects. Shown at a 1946 Tokyo meeting are: from left, seated, Drs. Nakahara, Henshaw, Sasaki and Brues; and from left, standing, Drs. Neel, Murati, Tsuzuki, Higashi and Ullrich.

Arriving in Japan in late November, our group of five was directed to conduct its activities within the Public Health and Welfare Section of General Headquarters (GHQ), Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers. Every activity in the Occupation had to have a proper title; it is my recollection that Dr. Henshaw first suggested we be called the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission.

Shown after a luncheon hosted by the mayor of Hiroshima on 6 December 1946, ABCC’s early cast of characters included: front row: a city official, Drs. Ullrich, Neel, and Tsuzuki; standing: Dr. Saida, a city official, Col. Johnson, Drs. Henshaw, Brues, Volk, Matsubayashi, and Block, as well as Dr. Omura, the official Japanese Welfare Ministry representative. Johnson and Volk were GHQ-assigned escorts.

Our little group spent about six weeks meeting with Japanese scientists in Tokyo, Osaka, and Kyoto. We surveyed the situation in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and in January 1947, the civilians and Lt. Ullrich returned to the States, leaving Block and me in a somewhat undefined situation. We decided to return to Hiroshima, where he, a surgeon-to-be, would try to determine some of the factors responsible for the keloid scars so prominent in some of the survivors, and I, in collaboration with another young medical officer–Lt. (j.g.) Frederick Snell, who had been released from duty at the naval base in Yokosuka–undertook to determine the hematological status of school children who had suffered epilation at the time of the bombing. I believe that the report by Snell, K. Ishibashi and myself on our findings was the first published under the ABCC imprimatur (Archives of Internal Medicine 84:569, 1949). During this period, I was also busy trying to develop a plan for a satisfactory genetics study.

In June 1947, I was ordered back to Washington to report to the Academy’s newly-formed Committee on Atomic Casualties. There followed a very busy three months, during which I submitted the plan for a genetics program to a special committee convened by the Academy. They accepted it, and I set to work to recruit my team, but I was also asked by the Academy to return to Hiroshima as the pro tem director of the ABCC, and this meant many conferences to decide upon the best way to proceed in occupied Japan. By the end of the summer, I had assembled a group of three: Dr. Masuo Kodani, a cytogeneticist; Richard Brewer, a data processor; and First Lt. Ray Anderson, a pediatrician, as the nucleus of the American genetics group.

Returning to Japan in September, I had dual responsibilities: on the one hand, to begin to generate the physical facilities necessary for the program, and on the other, to begin to implement the necessary scientific program and to recruit Japanese personnel. It is important to recognize that there simply was no precedent for a long-range epidemiological study of this nature; we had no model to emulate.

At that time, GHQ policy required that any U.S. activity work in close liaison with some corresponding Japanese organization. Col. Crawford Sams, chief of the Public Health and Welfare Section, GHQ, directed us to affiliate with the newly organized Japanese National Institute of Health, which then formed a Section on Atomic Bomb Effects. Of course, the JNIH had no previous experience with this type of research either.

It is difficult today to grasp the magnitude of the challenges we faced in 1947. The devastation of the bombings had left no suitable physical facilities for the study. Transportation and communication were difficult for both survivors and staff so that the ease of patient contact and scheduling that we take for granted today simply did not exist. But, far more important from the scientific standpoint was the fact that this would be a study without scientific precedent, which had to be organized so that it would be in keeping with Japanese culture and tradition–otherwise it could not succeed.

With respect to the physical facilities, I had to obtain both temporary space and begin to plan for more permanent facilities. Because it was thought that more than twice as many survivors had received significant amounts of radiation in Hiroshima as in Nagasaki, circumstances dictated that the major effort be mounted in Hiroshima. With respect to the temporary needs in that city, I negotiated for space in the Gaisenkan, on the Ujina waterfront. A former military assembly hall, it was far enough away from the hypocenter that it had escaped serious damage. It provided office facilities and an unused auditorium where we could stockpile material for the building ultimately to be constructed. It also could be accessed by sea, rail, or road and had adjacent space for a motor pool. During this same time period, I also enlisted the help of the city administration in finding a suitable place for a permanent facility. Our first choice was a former military area near the heart of the city. In this solution, I was later overruled by the consulting architect to the Academy, Sigmund Pfeiffer. The present location of RERF, atop Hijiyama, was certainly a more picturesque site than my selection of a “working class” area, but it presented both psychological and practical problems in those days of poor transportation facilities.

With respect to the research program, it was understood I would concentrate on getting a genetics program under way, while the Academy recruited personnel for medical studies on the survivors. Very early, we made contacts with Dr. Koji Takeshima, a young nisei (American-born) surgeon at the Red Cross Hospital, who was to be very important not only in helping us understand Japanese ways but in our recruiting of Japanese physicians. The plan I had developed, in collaboration with Dr. I. Matsubayashi of the Hiroshima City Health Department, required that we enroll all pregnant women in the two cities in our study when they registered their pregnancy with the city for ration purposes. When the pregnancies terminated, the midwives and/or physicians who attended the deliveries gave us a preliminary report on the outcome, whereupon one of our own staff physicians would visit the mother and examine the baby. I have long since forgotten how very many meetings I had with the midwife associations to enlist their cooperation and instruct them in the necessary procedures.

To put this plan in effect required developing a complex recordkeeping system. All this was finally in place by March 1948, and I returned to my position at the University of Michigan, having been relieved of my directorial responsibilities by Lt. Col. Carl Tessmer. You may be sure I had no thought at the time that the concerns of the genetics program would still be bringing me back to Japan in 1989.

This article was originally published in RERF Update 1(4):7-8, 1990.