Miller’s Memories of ABCC-RERF, 1953-1990 Part 3

Miller’s Memories of ABCC-RERF, 1953-1990: Part 3

by Robert W Miller

Clinical Epidemiology Branch, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, Maryland

The anecdotes of a longtime ABCC-RERF associate are concluded in this issue.

Child Health Survey, 1957-61

Jim Neel is a very talented organizer of large field studies. Advance planning would prepare us all to “hit the ground running.” Three young Japanese faculty members joined us and helped make the connections needed for approvals in Japan. Jim made sure everyone there who should know our plans was informed–from members of the Ministry of Health and Welfare and academic leaders, through officials of the local governments, to teachers and parents. We reviewed the literature, developed the procedures and tests to be used, met with key Japanese geneticists who visited Ann Arbor, and sidestepped some unexpected obstacles. Going back to school was as bad as I expected, but tailoring my activities to those of Neel’s Genetics Department diminished, or at least justified, the pain.

Morning review of the previous day’s medical charts for the Child Health Survey, 1958. From left: Jim Neel, and dentists Jerry D Niswander and Chokudo Sujaku.

We did hit the ground running. We quickly recruited an excellent staff of Japanese pediatricians, nurses, psychometric testers, and patient contactors. At least one of them, Masanori Otake, is still at RERF, where he built a career in biostatistics. Within 2 weeks, we were seeing 40 patients a day in the clinic. We finished in Hiroshima on schedule and soon after had a full clinic in Nagasaki.

My project was to be on a form of parasitism that caused 10% eosinophilia in 1 out of 4 Hiroshima children in 1955. When we returned in 1958, Japan had changed its agricultural practices, and the medical problem was gone. So I changed my topic to disturbances in visual acuity. My thought was that vision depends on perfect formation of the components of the eye, and imperfections due to inbreeding would be detectable by vision tests. This proved to be true, but overall the effects of inbreeding were not biologically significant except in families with known recessive traits–infrequent even in the large sample studied.

Some cases were unusually interesting. One tall girl only 8 years old almost pressed her eye to the page of a book as she waited to be examined. She had Marfan’s syndrome, as did nine other members of her family, who were among the tallest people in Nagasaki. Another child’s heart beat could not be heard until we listened to the right side of his chest. His little sister was peering at us from the end of the examining table. We listened to her chest and found she also had situs inversus. Both families were reported in the Japanese literature. All families were sent a letter describing the findings 4 days after the clinic visit.

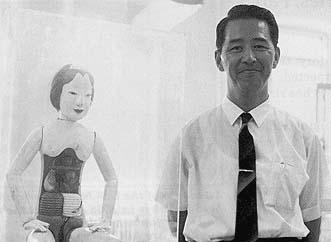

When reviewing x-ray films of the hand as a measure of maturation, we often noticed a malformed bone in the middle of the little finger. Its formal name is brachymesophalangy, but we called it “geisha finger” because of its x-ray image (see accompanying photo on p 8). Formal study by our group showed that in Japan it occurred in 10% of boys and 17% of girls, compared with about 3% in both sexes in the US.

anthropometrics being collected, 1959-60.

left, a malformed bone of the little finger, nicknamed “geisha finger” because of its x-ray shadow, unusually common in Japanese children.

right, in 1959-60, at the Nagasaki Laboratory, pediatricians in the child Health Survey. From left, Hiromi Tanaka; Kanji Iio; Shotaro Neriishi; Norio Fujiki, a hematologist and geneticist; Munetaka Miyake; and Noboru Yanai.

My thesis was accepted at the end of my second year at the University of Michigan. During that time, as Jim Neel reviewed the medical records he found they were detailed enough for him to use appendectomy scars as a measure of susceptibility to infection. There were no differences between inbred and outbred children.

Of the four Japanese pediatricians who worked with us in addition to Shotaro Neriishi, two obtained fellowships at Buffalo (NY) Children’s Hospital and one at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. I recently learned that our pediatrician from Kyushu University paved the way for five others from his school to follow him to Buffalo. One is now chairman of the pediatrics department at Kyushu University, and another is chairman at the school in Saga. Meanwhile Jim Neel helped establish studies of human genetics in Japan through the nucleus of young medical geneticists who worked with us.

National Cancer Institute, 1961 to the present

My natural place in epidemiology seemed to be in the study of birth defects, and the best opportunity proved to be at the US National Cancer Institute (NCI). I sought to use all of the information I had acquired–about pediatrics, radiation effects, and epidemiology–in the most clinical way possible. My lack of knowledge about cancer etiology may have been an advantage: I had no preconceptions about it. Very little attention had been given to childhood cancer etiology, and we made quick progress by means of descriptive studies of mortality (by age and race in particular) and by finding associations of certain cancers with specific birth defects. The syndromes we delineated or studied have since led to the identification of tumor-suppressor genes: Wilms’ tumor of the kidney and congenital absence of the iris of the eye, neurofibromatosis types 1 and 2, trilateral retinoblastoma (involving both eyes and the pineal gland), and the Li-Fraumeni cancer syndrome. Study of these rarities have led to understanding of how a substantial proportion of common cancers develop–cancers of the breast, colon, bone, and lung, among others. These findings belied the advice given to us 25 years ago: don’t study rare cancers because they have no public-health significance, and don’t study genetics because it can’t be fixed.

At a dinner party in 1964 in Bethesda, Maryland, I met a genealogist who thought that Hideo Nishimura, a teratologist and professor of anatomy at Kyoto University, and I would have common interests. Soon after, when Dr Nishimura visited Washington, we met, and we hit upon the idea of organizing a US-Japan workshop on teratology and childhood cancer in Tokyo. Although the National Science Foundation was funding only basic research, it approved our application for support of travel for five Americans, supplemented by others from ABCC (George Darling, Iwao Moriyama, William J Schull and Kenneth and Marie-Louise Johnson). Japanese funding came from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS). It proved to be a landmark meeting, for it encouraged the Japanese to extend their areawide childhood cancer registry in Tokyo to five other metropolitan centers, it set the style for a long series of US-Japan workshops on cancer, and it introduced teratologists from the two countries to each other, which led to many exchange visits by senior scientists, training of young Japanese in the US, and to increased studies of normal and abnormal development of human embryos. Three years later Dr Nishimura organized a Pan-Asian workshop in Kyoto on research methods in teratology, which produced an excellent set of proceedings and established Japan as an international force in teratology. Dr Nishimura was elected to the Japan Academy (Science) a few years ago.

Attendees of the US-Japan workshop on teratology and childhood cancer held in Tokyo in 1965 included the author (front row, sixth from the left) and co-organizer Hideo Nishimura (front row, second from right). Also pictured are ABCC Director George Darling (first row, fourth from right), present RERF Scientific Councilor Ei Matsunaga (second row, third from right), then RERF staff members Kenneth and Marie-Louise Johnson (back row, fourth and fifth from the left, respectively), and former RERF Permanent Director William J Schull (back row, third from the left).

During a visit to Hiroshima at about this time, I met Dr Michihiro Miyanishi of Hiroshima University, who worked part time at ABCC, and learned that, as an intern, he had asked a 30-year-old patient a seemingly naive question, “Why, when you are so young, do you have lung cancer?” The patient replied that it was probably because he had worked 10 years earlier during World War II at a plant on Okunojima that made mustard gas. Miyanishi and his professor, Sunao Wada, later a senior consultant to ABCC, visited the island and found another 18 former mustard-gas workers with respiratory-tract cancer. The study was not population-based and had not been reported in an international journal.

Michihiro Miyanishi in 1967 poses beside an antique Japanese anatomic teaching figurine. As an intern, his question to a single patient led to the discovery that wartime mustard-gas workers were developing respiratory-tract cancer at high rates.

We provided a modest 2-year contract that called for the fullest ascertainment possible of those exposed to the several poison gases made there and for determination of the frequency of cancer among the former workers. We published the results in Lancet in 1968: 33 deaths from cancer of the respiratory tract as compared with 0.9 expected. Since then the number of cases has risen to more than 75.

In 1971 the yen-dollar exchange rate fell sharply, and ABCC faced a fiscal crisis in meeting its expenses in Japan. At that time NCI had a year-end surplus of funds, and by formulating new tasks to be pursued at ABCC, we were able to make a contract that bridged the financial gap over the next 3 years. One purpose was to develop a visiting fellowship program in epidemiology for young Japanese who were faculty members in departments of public health. They would come to the US for a summer course in epidemiology and/or spend 4-6 weeks visiting NCI and other epidemiologic units. The balance of the year was spent in Hiroshima in the ABCC Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics working on a research project. Among the former fellows are Takesumi Yoshimura of the medical school in Kitakyushu, Kenichi Nakamura of Showa University, Kuniomi Nakamura of the National Institute of Industrial Health, and Mitoshi Akiyama, RERF Department of Radiobiology chief, who trained in immunology. The other new endeavor was to establish a tumor-tissue registry to monitor the occurrence of cancer in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The physicians in Hiroshima were interested, but it took time before several holdouts joined in and completed the coverage. The reluctant doctors in Nagasaki did not participate until the value of the system in Hiroshima was evident.

In 1972 we happened to be in Hiroshima when George Darling retired, and we participated in the celebration of his 15 years at the helm of ABCC. During the following year, when he was a Fogarty Scholar at NIH, I suggested to Richard Remington, dean of the School of Public Health at the University of Michigan, that he consider Dr Darling for an endowed lectureship on international public health. Instead he was awarded an honorary degree.

In February 1975, I was a member of the Crow Committee, which evaluated the accomplishment and potential of research at ABCC just before it became RERF. A comprehensive report was prepared (JF Crow et al, ABCC Technical Report 21-75), but it was impossible to match the impact of the report by the Francis Committee 20 years earlier (see “Miller’s Memories, Part 2,” RERF Update 6[1]:9-10, 1994). The most memorable event of this visit was my departure from Hiroshima on a wintery night. Alone on the train platform on my 20th wedding anniversary I watched the snow falling gently. A soft voice called to me from behind. It was Celina Rappaport, who had come to say goodbye in place of her father [then ABCC-RERF business administrator Mick Rappaport], who was ill.

Postscript

In 1974 NCI had entered an agreement with JSPS to establish a US-Japan Cooperative Cancer Research Program, which provided for short-term exchanges of mid-level scientists, of materials such as drugs, and of ideas–through numerous workshops. Since 1979 the program has involved four subject areas: etiology and carcinogenesis, biology and diagnosis, treatment, and interdisciplinary studies. Haruo Sugano, president of the Cancer Institute in Tokyo, and I have been the coordinators of the interdisciplinary area. We have had two workshops per year featuring differences in cancer occurrence in the two countries. There have been three on lymphoma and other lymphocytic diseases, which are of interest because the Japanese have lower rates for B-cell lymphoma but higher rates of autoimmune disease than do US Caucasians. Whatever protects against B-cell lymphoma in Japanese seems to predispose them to autoimmune diseases. Koji Nanba of Hiroshima University made good use of the tumor-tissue registries to show that the rates of lymphoma in Japan differ greatly from US rates.

We have held four workshops on biostatistics that proved to be especially beneficial to RERF. Three were in Hiroshima, because it is the biostatistical center of Japan–few academic positions for biostatisticians exist elsewhere. Our objective was to enhance interest in the field. David Hoel’s attendance at one of these workshops led him to spend two terms at RERF as a director and to accept several Fellows from Japan for training at the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina. Takashi Yanagawa of Kyushu University, who has trained extensively in the US and Australia, has emerged as the Japanese leader of the workshops. I co-organized the first of the series with his mentor, Akio Kudo, who said to me midway through the program, “You have to realize, Dr Miller, that in Japan mathematics is 2000 years old and medicine is only 200 years old. You can’t rush them into a marriage.”

In 1981, after serving on various committees of ABCC-RERF, I was appointed to the Scientific Council, which made it possible for me to return annually for 9 years, enabling me to keep abreast of developments, offer suggestions about new studies, and provide the council with an institutional memory going back more than 30 years. My career and those of others who have served ABCC-RERF have been well served in return. On-the-job experience there has produced a small army of radiation experts, epidemiologists, biostatisticians, and human geneticists for Japan and the US.

Part 1 of Robert Miller’s recollections appeared in RERF Update 5(4):7-9, 1993, Part 2 was published in RERF Update 6(1):9-10, 1994, Part 3 was published in RERF Update 6(2):8-10, 1994, and Part 4 was published in RERF Update 9(2):12-14, 1998. On 27 April 1994, Miller became a scientist emeritus at the National Cancer Institute.