Miller’s Memories of ABCC-RERF, 1953-1990 Part 2

Miller’s Memories of ABCC-RERF, 1953-1990: Part 2

by Robert W Miller

Clinical Epidemiology Branch, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, Maryland

The anecdotes of a longtime ABCC-RERF associate continue.

Problems in scientific communication

I stayed at ABCC an extra 6 months and rushed to prepare a report on findings among children in the decade after the bombings for presentation at the spring meeting of the pediatric research societies in the US. I am still shocked that the paper was not accepted for presentation, perhaps because it was not a conventional subject for pediatric research. A similar experience occurred in Japan. At the special quadrennial meeting of the Japan Medical Association, as a distinguished foreign visitor, I was scheduled to speak on the late effects of the atomic bombings on children. ABCC had long been accused of withholding information, so here was a chance to show we had nothing to hide. Virtually no one came to my lecture because at the same time there was a lecture on ekiri, a common life-threatening diarrheal disease thought to be unique to children in Japan. Ten years later, on the 20th anniversary of the bombings, journalists searched for something new to report and discovered the effects of exposure on the fetal brain.

Matrimonial pursuits

The 6-month extension allowed me another pursuit–of my future wife. I had purposely signed a 1-year contract because I thought I would probably be socially limited in Japan. I had no clue that Japanese women would be so attractive. The main tourists to Japan had been millionaires, who had not spread the word as later visitors did. For me the fairest of all was Haruko Nakagawa, whose personality has blended with mine for 39 years so far. She had been given an English name at a New Year’s Day luncheon at the Bachelor’s Officers Quarters, the predecessor of Hijiyama Hall, which was built in 1953. Someone suggested that for foreigners she needed a name that was easier to remember. Holly seemed the diminutive of Haruko and was appropriate to the Christmas season. She accepted it after first objecting that it is a man’s name, like Harry Truman. Seven weeks later we were married at the US consulate in Kobe. The day we married the roof fell in–the roof of the hondori [the covered shopping street] in Hiroshima had been built to hold 6 inches of snow and on that day 7 inches of snow fell.

The ‘Hiroshima maidens’

Just before we left for home in May 1955, Norman Cousins, editor of The Saturday Review of Literature, and William M Hitzig, an internist, came to Hiroshima to select 25 young women to bring to New York for surgery to diminish their disfiguring keloids due to burns. Cousins and Hitzig were late in looking for someone to serve as a cultural liaison for the “Hiroshima maidens” while they were in the hospital and between admissions, when they were to live with nearby Quaker families. While visiting the Department of Medicine at ABCC, Cousins mentioned the need for such a person as he stood beside the desk of the perfect candidate, Hatsuko Yokoyama (known to the American staff as Helen), who was performing just that function for ABCC internists and their patients. Helen, born in the US, had graduated from UCLA with a degree in psychology and had returned to Japan. Her initial uncertainty about accompanying the Hiroshima maidens was overcome when she met them and saw their plight. Her travel documents were in order, so she could leave immediately. In New York there were, as expected, many problems during the course of the year, as we learned during visits with Helen that have since been partially described in two excellent books, The Hiroshima Maidens, by Rodney Barker, and Faces of Hiroshima, by Anne Chisholm.

When the “Hiroshima maidens” journeyed to the United States for medical treatment in 1955, Hatsuko Yokoyama (seated in the front row to the right of the girl with braids), an ABCC Department of Medicine staff member, served as the cultural liaison.

I wish that Helen, who lives in retirement near Hiroshima, had written the story behind their stories, known only to her. Without her, the heroic endeavor would likely have failed, as it did subsequently when others tried to repeat it.

National Academy of Sciences, 1955-1957

We returned to Rochester, NY, in early June 1955, and I was unemployed for 4 months because no one needed a pediatrician who specialized in radiation effects. The field was too narrow. Word came that Tax Connell was leaving his position as the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) professional associate for ABCC. I assumed the position on a month-to-month basis and stayed for 2 years. My boss was R Keith Cannan, a biochemist and a superb administrator. He was chairman of the NAS Division of Medical Sciences and a master of committee management. He sat in on many committee sessions, making suggestions that moved the deliberations along and, when necessary, rewrote reports that would have fallen short of the Academy’s high standard. He was a wonderful mentor.

Just after I arrived at NAS, he and the three-person Francis Committee left for Japan, where ABCC was near collapse scientifically. Thomas Francis Jr had just finished the landmark field trials of the Salk polio vaccine. He was an expert in acute-disease epidemiology, but could he adapt to the idea of long-term studies of chronic diseases? The other two members of the team were Seymour Jablon, a statistician in the Medical Follow-up Branch of NAS, and Felix Moore, chief statistician at the National Heart Institute. Previous advisors to ABCC had been academic medical specialists whose visits to the clinics in Japan were more ceremonial than substantive. Cannan, a basic scientist, was the first to appreciate that ABCC needed expert advice on epidemiology. The Francis Committee spent 3 weeks collecting information and then formulated the scientific design that still serves as the basis for the studies of the Radiation Effects Research Foundation. It was a stunning consultative success.

In 1957 the name of George B Darling, professor of epidemiology at Yale University, arose as a candidate for the directorship of ABCC. Cannan spoke to him about scientific and administrative matters, and I told him and his wife about life in Japan. They accepted the offer for 2 years and stayed 15. Darling implemented the recommendations of the Francis Committee and greatly improved not only productivity but also congeniality at ABCC. The contributions of Cannan, the Francis Committee, and Darling have been covered from other points of view in RERF Update by S Jablon (3[1]:5-7, 1991), H Maki (3[3]:7, 1991), and K Joji (ibid, p 8).

Cannan also arranged for rotation of staff from academic departments in the US through ABCC. Yale provided internists, UCLA pathologists, and NAS biostatisticians. He went to his friend, James Shannon, director of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and arranged for public-health officers recruited to NIH to be assigned as junior staff members to ABCC for 2 years. Among them were Robert M Heyssel, who went on to become executive vice president and director of Johns Hopkins Hospital, and Gerard N Burrow, who is now dean of the Yale Medical School. My job was to provide Cannan with medical advice, to speak on radiation effects found at ABCC, and to recruit staff from the US.

From my experience in Japan, I realized my interest was in epidemiology, which is relatively rare among physicians. By brief formal training in this field, I could broaden my horizons. Going back to school, though, was unthinkable. Then James V Neel visited Cannan to tell of his idea, with William J Schull, of comparing the health of children of consanguineous marriages [eg, marriages between cousins] with that of outbred children who had been among the 72,000 people examined in the ABCC genetics study, but in the non-exposed group. At the time, about 7% of marriages in Japan were between cousins. About 3800 inbred children and an equal number of outbred children would have comprehensive medical examinations.

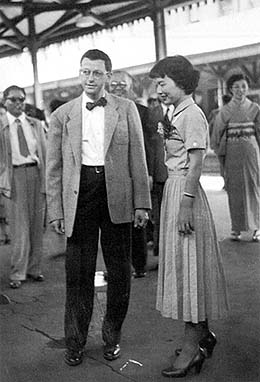

In 1955, ABCC colleagues and friends (including physician and well-known author Michihiko Hachiya, seen in the background between the Millers) bid farewell to the author, left, and his bride, Holly.

A chief of pediatrics was needed to help with the planning, for 1 year in Ann Arbor, to be followed by a year each in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and then back to Ann Arbor for a year in analyzing and reporting on a study of my own. During the first year in Ann Arbor, I would be a candidate for a master’s degree in public health, and during the last year would write a dissertation to qualify for a doctorate degree in public health. Cannan invited me to a farewell luncheon at the Cosmos Club, just the two of us and our wives. About 20 members of the division were there–truly a surprise party. We left for Ann Arbor in September 1957.

Part 1 of Robert Miller’s recollections appeared in RERF Update 5(4):7-9, 1993, Part 2 was published in RERF Update 6(1):9-10, 1994, Part 3 was published in RERF Update 6(2):8-10, 1994, and Part 4 was published in RERF Update 9(2):12-14, 1998. On 27 April 1994, Miller became a scientist emeritus at the National Cancer Institute.